The spark behind the concept

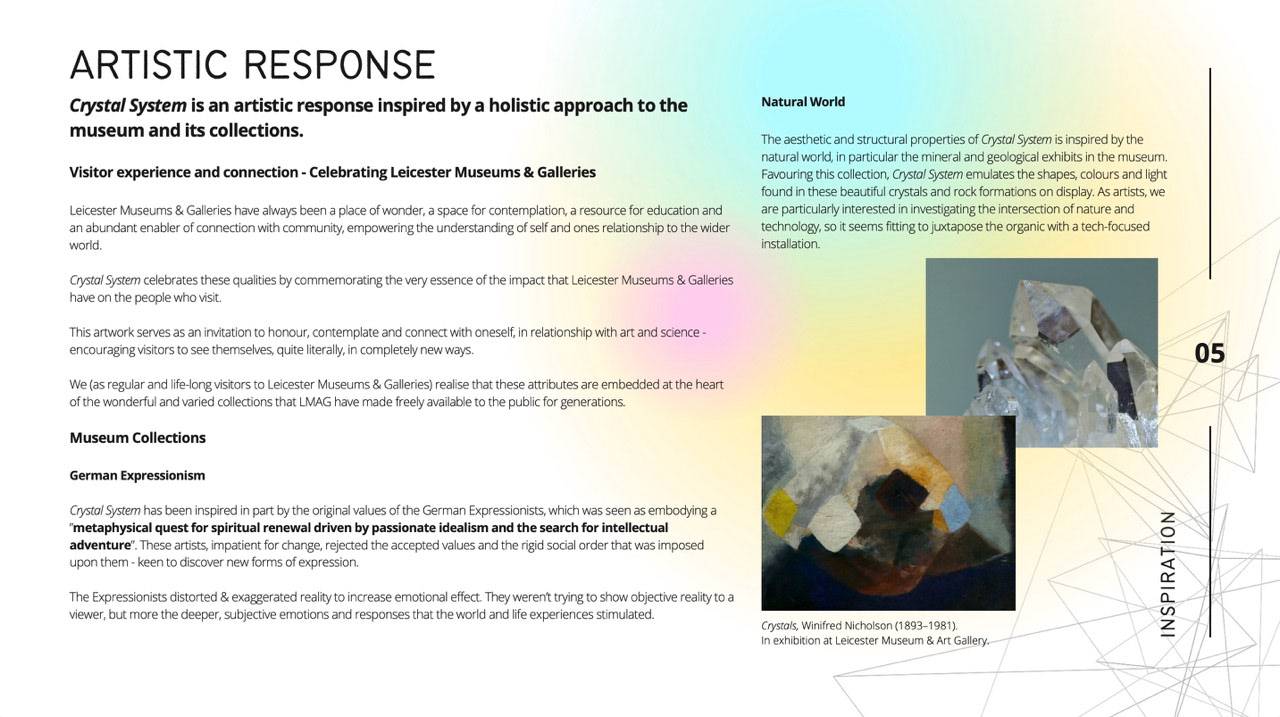

When we first encountered the brief, we'd found ourselves in Leicester Museum's checking their geological collection. Winifred Nicholson's painting "Crystals" from the museum's collection was a definitely an early inspiration point. There's something magical about how crystals grow - these perfect mathematical structures emerging from chaotic natural processes. We found ourselves returning to one question: what if we could capture that moment of transformation when raw material becomes something structured and beautiful?

The thinking wasn't just aesthetic. Leonie had realised crystals represented exactly what we wanted the artwork to do - take scattered individual visitors and create moments of structured, shared experience. Each person would become like a molecule in a growing crystal, their movements and interactions building something larger than themselves.

Coming back to Winifred Nicholson's painting "Crystals" from the museum's collection and looking at how she'd broken down those mineral forms into geometric colour relationships, we started thinking about breaking down visitor experience in the same way - into distinct sensory moments that could be recombined through interaction.

Winifred Nicholson's painting "Crystals", located at Leicester Museums and Galleries

Wrestling with the fundamental questions

Early in our process, we found ourselves trying to get to grips with questions like - how do you make technology feel natural rather than imposed? How do you create genuine surprise in an age where people expect everything to be interactive?

We spent endless amounts of time debating what the piece should actually do! As an audiovisual artist, I naturally focus on the technical possibilities and tool, and all the different ways sensors could respond to human presence. Leonie kept pushing us to think about why someone would want to engage with it in the first place. The breakthrough came when we stopped thinking about sensors as input devices and started seeing them as hidden musicians in an invisible orchestra.

Leicester Gallery also has an outstanding collections of German Expressionism - one of the best in the world. I spent a lot of time immersed in that room. I find their work bold and futuristic, so it's only natural that a German Expressionist connection emerged from this thinking. Like those artists who distorted reality to reveal emotional truth, we wanted to distort visitors' normal relationship with space and reflection. Every mirror surface became a potential disruption of expectation. Instead of just showing you your reflection, what if the artwork could show you yourself transformed - multiplied, colourised, responding to your presence in ways that felt almost magical?

We started to realise that we weren't just making an interactive sculpture. We were designing a system for transformation - both optical and psychological. The crystal metaphor became our guiding principle: raw input (human movement, sound, presence) gets processed through our geometric system and emerges as something structured and beautiful.

Making the invisible visible through design decisions

Once we had our conceptual framework, the real challenge became translating these abstract ideas into physical reality. Our first major decision was rejecting the idea of obvious interfaces. No buttons, no screens, no instructions. We wanted the interaction to feel discovered rather than directed.

This led us deep into material experimentation. Leorie had worked with acrylic before and already know about how dichroic films behave under different lighting conditions. So we had a head start with the materials.

Sound design became complex. Leonie developed a base soundscape that needed to feel meditative but not boring, present but not intrusive. Then we layered interactive elements that would harmonise with the base rather than fighting it. Every triggered sound had to feel like a natural extension of the ambient environment, not a jarring addition.

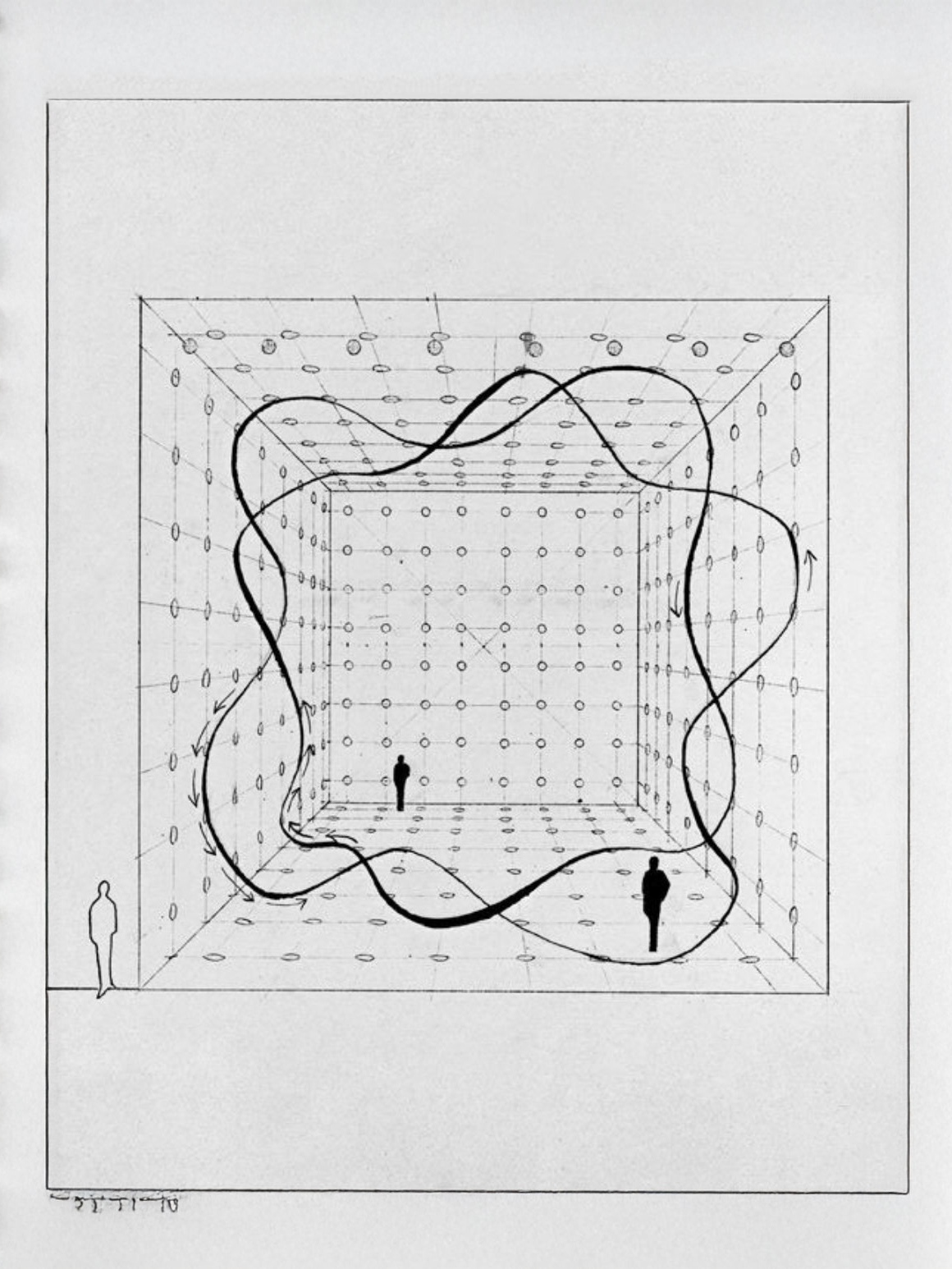

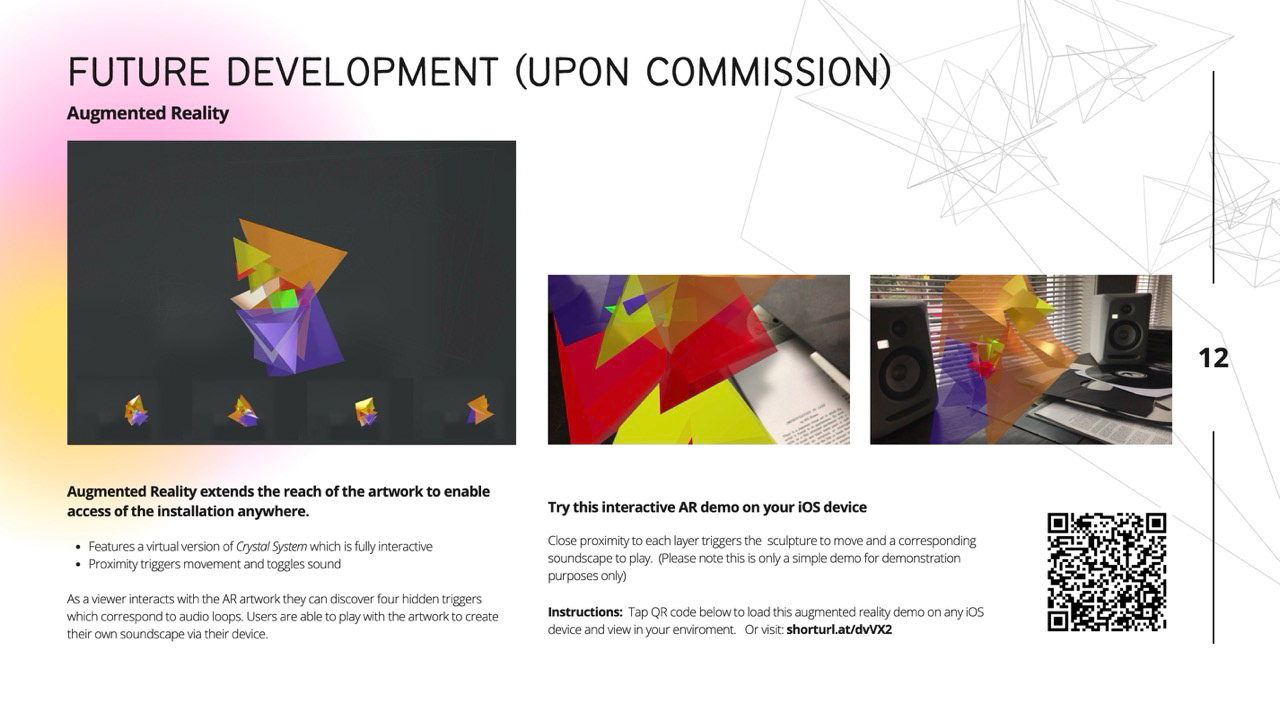

sample page from proposal

sample page from proposal

sample page from proposal

sample page from proposal

Navigating the collaborative creative process

Working as a duo on this project forced us to constantly articulate and defend our ideas. My background in technology meant I thought in terms of systems and possibilities. Leonie's focus on emotional response and accessibility meant every technical decision got challenged. There were some challenging days!

The collaboration with ArtReach and Leicester Light Festival added another layer of creative constraint that actually helped focus our thinking. The public festival context meant we couldn't create something too precious or fragile. It had to be super solid, robust. The family audience meant we needed to consider accessibility not just as an add-on, but as a fundamental design principle.

Working with the technical team taught us huge amounts about the gap between concept and reality. What seemed simple in our sketches required extensive programming, careful calibration, and robust building. Each technical challenge forced us to refine our artistic vision.

From digital models to physical reality

The dichroic film application process became almost meditative. Each piece had to be applied without bubbles or wrinkles, positioned exactly to catch light at the right angles. We realised we were essentially creating large-scale jewellery! Every surface needed to be perfect because visitors would see it multiplied infinitely through reflections.

Revelations

The biggest lesson we learned was about the difference between interactivity and responsiveness. Initially, we thought we were making an interactive artwork - something people could control and manipulate. What we actually created was something responsive - an environment that acknowledged and celebrated human presence without necessarily giving people direct control over the experience.

Visitors didn't need to master the system or understand its rules. They could simply exist within it and feel recognised by it. The sensors weren't providing control mechanisms; they were creating moments of technological empathy.

Experimenting with the diachronic film

Revelations ( cont )

Our material experimentation taught us that optical effects can't be fully predicted or controlled. Dichroic films behave differently under various lighting conditions, creating effects we never anticipated in our tests. Rather than seeing this as a problem, we learned to embrace the unpredictability as a feature. The artwork continued to surprise us even after installation.

The collaborative process revealed how important it is to have someone constantly challenging your assumptions. Working alone, either of us might have created something technically impressive or aesthetically pleasing, but probably not both. The tension between our different approaches forced us to find solutions that satisfied multiple criteria simultaneously.

Building for a festival environment taught us about resilience in interactive art. Systems need to be robust enough to handle enthusiastic interaction while remaining sensitive enough to feel responsive. Weather conditions, varying crowds, and extended operation periods all test your work in ways that studio development can't replicate.

Perhaps most importantly, we learned that successful interactive art doesn't just respond to people - it changes how people respond to each other. The most memorable moments weren't when someone triggered a beautiful effect, but when that effect became the catalyst for social interaction, shared wonder, or collaborative play.

Exhibition Journey

Crystal System was exhibited three times throughout 2022, each venue bringing its own context and audience to the work. The piece was originally commissioned by ArtReach for the LightUp Leicester Festival, where it found its home among families and festival-goers discovering interactive art at Beta X. Later that year, it traveled to the Institute in Loughborough as part of Loughborough Lates, where it engaged with a different demographic in a more intimate gallery environment. Finally, it concluded its exhibition run at the LCB Depot as part of an architectural programme in late 2022. Each location taught us something new about how context shapes interaction - the same artwork revealing different facets of itself depending on the space, the lighting, and the expectations of its audience. These multiple exhibitions reinforced our understanding that responsive art doesn't just adapt to individual visitors, but transforms based on its entire environmental and social context.